| ||||

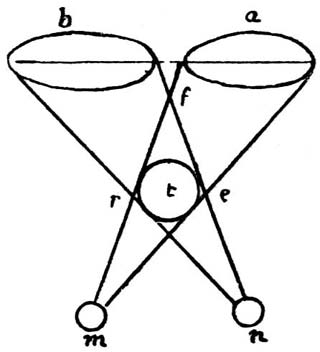

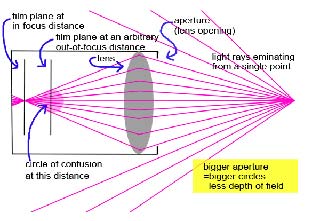

The following information is inspired by the lecture that Perry Hoberman, Research Fellow in Interactive Media, gave as part of our Fall 2007 Animation Seminar at the University of Southern California, and by research conducted by our student panel over the course of the semester. A basic explanation of the image to eye to brain process, excerpted from an article on the US Navy (IVRD) project , is: "The two eyes provide slightly different views of the same scene. Information from the left visual field goes to the right side of the retina in both eyes. At the optic chiasm, half the nerve fibers from the left eye cross over to the right hemisphere and the rest stay uncrossed, so that all the information from the left visual field ends up in the right hemisphere. In this way, a given hemisphere gets information from the opposite half of the visual world…"  Image courtesy of Howard Hughes Medical Institute Eyes focus in their sockets to converge on different objects at different distances. The object your eyes are converged upon is seen as one single object with some level of depth. Everything else you are seeing is perceived as a double image - you just don't think about it or aren't aware of it. If you're focused on a particular point in your central field of vision, your entire visual world becomes correlated to that point, called the Horopter. Beyond that correlated point, everything is uncrossed (L brain sees what L eye sees, R brain sees what R eye sees), meaning that we don't see it in stereo. In front of that, everything is crossed. Artists as far back as Leonardo Davinci have been fascinated by studying how our eyes & brains process information. Click on his drawing below to see an excerpt from the Davinci Notebook studies:  Stereo vision allows us to perceive the world with depth, or in 3D. Our peripheral vision does not see in stereo and is therefore 2D. The difference in information between what each individual eye perceives peripherally is too varied and wide apart to be able to be crossed into a single stereo image by the brain. Though I haven't specifically researched this, it seems that the process of perceiving information from our periphery uses an instinctual, intuitive, and less focused part of the brain than frontal focused vision. I would also argue that this is type of perception is probably similar to the soft-focus type of relaxed vision practiced during open-eye meditation techniques or experienced by athletes who describe moments of being "in the flow". It is being perceptually aware of the entirety of the visual field without deliberate focus on any one particular thing. To see how wide your peripheral field of vision is, try this test here! Within near vision, however, we have a highly acute sense of stereo perception. According to Perry Hoberman, there is a theory that we may have developed stereo vision in order to differentiate depth in near textures. As our eyes rotate and correlate the separate images from each eye into a united image at a specific point, the brain perceives the distance relationship between each object to us, translating it into our perception of focal depth. We can understand this by thinking of depth-of-view in a camera. As we focus the lens at different points in a scene, we have a sense of how close or far an object is based on whether it is in focus or blurry. We assume the blurry objects are far away or super close. The camera calculates the focus point as the distance in feet from the lens to the object. Similarly, our brains calculate distance based on the angles at which our eyes converge and rotate at focal points.  for more of an explanation on camera depth-of-field, see here. The major difference between stereoscopic images and our perception of the world is that when we perceive the world, muscles simultaneously rotate our eyes to converge and also to focus on an object. With Stereoscopic images, the eyes still converge images to see things either in front of or behind the screen, but they remain focused at a fixed point, the screen. As a result, with stereo, the muscles that rotate the eyes are decoupled from those that focus the eyes. Because the act of perceiving becomes slightly unnatural, the images can't really be called realistic.  According to Perry Hoberman, Stereoscopic images are a strange something in between an image and an object. Artists, like Hoberman, are more interested in examining the dynamics of these eerie virtual spaces than in necessarily trying to recreate reality. Stereoscopy and other forms of virtual reality literally force the biological mechanisms of our eyes to perceive in new ways. This optical play opens up an interesting dialogue between how visual imagery can influence or trick the brain at a multitude of different levels. It also helps us to understand exactly how the senses perceive, often through studying what does not "seem" real. See some of Perry Hoberman's work here:

VR and Interactivity Perry Hoberman |

[page 1] [page 2] [page 3] [page 4]

Return to main Page